Can the Paris 2024 Olympics really avoid a construction budget overspend?

01 July 2024

The organisers of the Paris 2024 Olympic Games are hoping to keep construction costs and carbon emissions within strict budgets. Lucy Barnard takes a look at this summers “lean” Games.

The newly constructed Olympics Aquatics Centre in the Paris suburb of Saint Denis may be gearing up to host the world’s top divers and artistic swimmers this summer, but for the moment, all eyes are on the seats.

The Paris 2024 Aquatics Centre. Image: Paris 2024

The Paris 2024 Aquatics Centre. Image: Paris 2024

The 5,000 shiny white seats at the curved, wedge-shaped venue, which connects to the neighbouring Stade de France via a footbridge spanning the A1 motorway, have been made from recycled plastic collected by more than fifty recyclers who collect and sort packaging waste from the many thousands of yellow recycling bins into which Parisians dump their trash.

And that’s not all. This summer’s Olympic Games, scheduled to take place between July 25 and August 11, have already been dubbed the “lean” Olympics due to a strict insistence of keeping within both cash and carbon budgets as organisers promise to deliver a new low-construction Games.

To this end, organizers say that their key goals are to keep costs low, to balance the budget so that almost all of the money needed to host the event comes from its own sources of income such as ticket sales and sponsorships - and to reduce the carbon footprint to less than half of that for previous games.

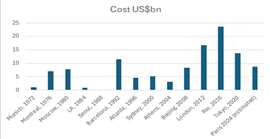

The reason for this is all too clear: Spiralling costs are putting cities off bidding to host such events.

Although estimates for total spend vary considerably, economists estimate that London’s 2012 Olympics overspent by more than US$5bn. But that pales in comparison with Tokyo 2020 where the budget overran by nearly US$26bn after the Covid pandemic forced an eight-month delay and then spectators were not allowed. And the State of Rio de Janeiro was forced to default on its debts after it hosted the Games in 2016 (see chart below).

In July 2023, the Australian state of Victoria surprisingly cancelled the 2026 Commonwealth Games due to increasing costs and less than a year later, media reported that Brisbane had considered pulling out due to cost overruns.

And the eye-wateringly high carbon footprint produced by the Games has led some environmentalists to suggests breaking the event up and staging different disciplines in various cities meaning fewer spectators travelling by plane.

Spiralling costs and carbon emissions

With 10 million spectators and 15,000 athletes expected to flock to the event, many flying from overseas, the lion’s share of the carbon footprint of the Games is likely to come from aviation - something the organisers can do little about.

Instead, the key way in which Paris says it is hoping to meet both these ambitious targets is by cutting as much construction as possible from the Games.

Rather than treating the Olympics as an excuse to splurge on building venues, arenas and other infrastructure, this time around organisers say the plan is to keep building and carbon costs to a minimum by reusing venues and materials, recycling where possible and ensuring that everything is done as sustainably as possible.

The new Aquatics Centre in Seine Saint Denis, Paris. Photo: Paris 2024

The new Aquatics Centre in Seine Saint Denis, Paris. Photo: Paris 2024

Unlike the major building projects of the Rio, London and Tokyo Games, 95% of the sites that will be used in Paris are existing venues or temporary structures.

Paris 2024’s main outlays have been just three major builds - The Aquatic Centre in Saint-Denis which is expected to cost €175 million (US$190.6m), the Porte de la Chapelle Arena costing €138m (US$150.3m), both of which have been built by a consortium led by Bouygues Batiment Ile de France - and the city’s vast new Olympic Village built by French multi-national Saint Gobain, which has been budgeted at €1.5bn (US$1.64bn).

The rest of the events will take place in existing sports stadiums such as the Stade de France or in temporary venues such as a new urban park which has been created in the Place de la Concorde to host basketball, skateboarding and BMX freestyle.

Despite a series of strikes by some construction workers last year, organisers say that all three projects have now been completed and handed over ready for the games.

Together these three projects have a budget of around €4.5bn (US$4.9bn) – roughly half the overall which the organisers are hoping to spend on the event.

Moreover, organisers say that all three projects have been built to the smallest carbon footprint possible.

The Aquatics Centre has been built predominantly from wood, showcasing a recent French sustainability law which requires all new public buildings to be built from at least 50% timber or other natural materials. The building’s 5,000 square meter roof is covered with solar panels, making it one of France’s largest urban solar farms, enabling it to generate 20% of all the required electricity for the building.

Similarly the Porte de la Chapelle Arena (now christened the Adidas Arena) has been built using low carbon concrete using an onsite concrete batching plant which enabled the composition of the concrete to be adjusted on a daily basis according to the weather and the needs of the site.

Historic Olympic Games outrun costs. Source: Flyvbjerg and Budzier, May 2024

Historic Olympic Games outrun costs. Source: Flyvbjerg and Budzier, May 2024

And, the Games’ centrepiece Olympic Village, a series of roughly 40 low-rise tower blocks, spread across Saint Denis, Saint Ouen and L’Île Saint Denis on 53 hectares of land, has been built as a low carbon neighbourhood designed to be converted into homes after the event, with at least a third to be public or affordable housing.

The site, which was handed over in February, includes its own mini water treatment centre to collect and purify wastewater which can then be used to water the gardens and has been built with high performance insulation and sunshades as well as reversable underfloor plumbing designed to heat and cool the buildings without the need for air conditioning. Unfortunately for Paris 2024, this final measure has caused great controversy, with a number of Olympic teams saying they intend to sidestep the issue and bring their own portable air con units for the comfort of their athletes.

And, in an attempt to move towards more sustainable energy use, all of the sports venues will be connected to the national grid, meaning that stadium operators will not have to rely on diesel generators for power.

Of course the final score in terms of both budget and carbon will not be known until after the competition ends. The French Court of Audit has been asked to provide a final report on the event by autumn 2025.

The event’s initial budget was set at €6.8bn (US$6.9bn) in 2018 but in the French government has raised that twice to €8.3bn in 2022 and to around €9bn this year.

Around half of Paris’ budget has been allocated to the 2024 organising committee (Cojo) which is in charge of managing the competition, tickets and security. The other half has been allocated to the Olympic Delivery Company, Solideo, which is responsible for building the facilities.

The design for the Paris 2024 Olympic Games venue at Place de la Concorde. Image: Paris 2024

The design for the Paris 2024 Olympic Games venue at Place de la Concorde. Image: Paris 2024

So far, French officials say they are optimistic that they can cover any additional expenditure.

Last month, Cojo chief executive Etienne Thobois told reporters that the body expects to at least break even and may even make a small profit on staging the event.

“Everyone has been conscious of every euro that is spent, that is useful and we should be careful not to spend any euros on things that are superficial. Frankly that is a challenge in itself,” he said.

Thobois said that both Cojo and Solideo had agreed to only spend the amount that can be generated from the event in terms of revenue.

“We have kept some contingency, and hopefully, we will not use all of the contingency, so it will be a little plus at the end, but it will be marginal,” he added.

But others are less so sure. Historically, the bill for Olympic Games expands in the latter stages of preparations as unbudgeted costs appear or extra funds are needed to accelerate building work.

In March, Pierre Moscovici, the first president of the Court of Auditors told France Inter Radio that the ultimate cost to taxpayers is likely to be between €3bn and €5bn.

Bent Flyvbjerg, a Danish economic geographer who tracks construction budget overspends, calculates that although its rigid adherence to a reuse and retrofit policy has led Paris 2024’s cost estimates to fall below those of the three most recent Summer Games, they still stand US$1.32bn more than the historic median.

“So far Paris 2024 has had a 115% cost overrun in real terms, which places them in the middle range of previous summer games with a substantial risk of further overrun,” Flyvbjerg says in a study published at the end of May 2024. “Paris 2024 is a first in terms of reuse/retrofit and perhaps it will take time before the new policy matures and becomes effective, meaning that future Games could have a lower cost than Paris. The IOC will certainly hope so in order to give potential host cities less reason to walk away from the Games due to high costs.”

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM